The following is a testimony from Joy Schmidt Pople, who joined the Unification Church in Washington, D.C. in July of 1970 and was part of the “One World Crusade” in 1972. She turned down offers of professional positions at the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution in exchange for years of a nomadic life that included campaigning, pioneering, and publishing. After four months on One World Crusade, Pople boarded a bus for Mississippi with $100 in her pocket to spend a year teaching the Divine Principle and hosting more bus teams, which by then were part of a program called the “International One World Crusade,” having been joined by European and Japanese Unificationists. She, her husband, and their two children now live near Syracuse, New York, where she keeps grounded by tending the vegetable-, berry-, and melon garden in their back yard.

Rev. Sun Myung Moon came to America just before Christmas of 1971, called the faithful to him, and announced plans for his first public speech, to be given at Alice Tully Hall in New York City, on February 3, 1972. About 75 disciples were raptured from centers around the country to study at his feet and spread his message to Americans. Throughout a cold January, we stood on Manhattan street corners in snow and sleet selling tickets for three speeches by a Korean prophet whose only claims to fame at that time were founding a Korean children's folk-dance troupe and marrying 777 couples at one time in 1970.

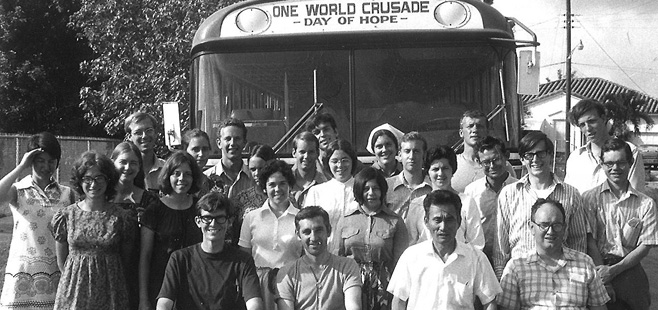

One World Crusade team in Miami, Florida, in June 1972. Front row, left to right: Perry Cordill, Jon Shuhart, David S.C. Kim, Ernest Stewart. (Photo courtesy of Margaret Herbers)

We took over a house in the Bronx for sleeping quarters. Rev. and Mrs. Moon, who were beginning to feel like “True Parents” to us, and their entourage slept on the first floor, the sisters on the second floor, and the brothers in the basement. For meals and lectures, each morning we descended more than a hundred steps to a little rented church building, where we ate a simple breakfast and listened to President Young Whi Kim, head of the Korean Unification Church, lecture the Divine Principle. Sometimes Father spoke to us afterwards. Then we rode the subway to spend long hours each day in Manhattan trying to sell $18.00 tickets to the three-night program.

We stood on the heating vents of the sidewalk, waylaying passersby with invitations to the program. If they said no, we sometimes followed them as far as 40 city blocks, just in case they should change their mind about buying tickets. Some people gave us money just to get rid of us. Long before it became fashionable, we dressed in layered outfits, piling clothes on top of each other trying to protect ourselves from the 70-mile-per-hour gales blowing between the skyscrapers. Father and Mother sometimes showed up unexpectedly at a street corner to chat with one of their followers. Those who sold a ticket during the day were allowed to return to the little church for dinner; the rest of us had to stay on the streets until 9:00 p.m., when we returned to exchange stories about the day and eat some hot food. During this difficult month, we began to learn about praying with a desperate heart and begin to taste Heavenly Father's longing to connect with His children.

By the opening program on February 3, 1972, a few hundred tickets had been sold, and in a near blizzard we waited at the doors of the Lincoln Center for our long-sought guests. Only the first few rows were filled with living, breathing human beings. Some of us saw angels occupying the remaining seats.

In Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Berkeley, the scenario was repeated, each time with a bit less snow, somewhat cheaper tickets, and a few more guests. The standing-room-only audience at the Claremont Hotel in the sunny hills of Berkeley had paid only $2.00 admission.

When this campaign ended in mid-March, Father announced his desire to send pioneers to the approximately 40 states that had no Unification Church center. The 75 disciples submitted names of those among their number best suited for pioneering. The rest were divided into two traveling teams, one led by Miss Young Oon Kim visiting the northern half of the United States, and the other led by Mr. David Kim visiting the southern half of the United States. Originally named Sang Chul Kim, Mr. Kim chose the Western name, “David,” to exemplify his lifelong devotion to fighting for God and against evil.

Not being nominated for state pioneering, I became part of the mobile team called One World Crusade.

Life as a One World Crusader

Members who were part of the seven-city tour campaign

January-March 1972 in a photo with Father, Mother, and Mrs. Won Pok

Choi: Left to right: Izilda Lima (Withers), unknown, Jackie Brown,

Joy Schmidt (Pople), Patricia Kieffer (Fleischman), and Nancy

Callahan (Hanna). (photo courtesy of Joy Pople) Members who were part of the seven-city tour campaign

January-March 1972 in a photo with Father, Mother, and Mrs. Won Pok

Choi: Left to right: Judy Barnes, Olivia Kerns, Elizabeth Mikesell,

Jeannine Hancock (Grahn), Gerry Porcella (Linek), and Margaret

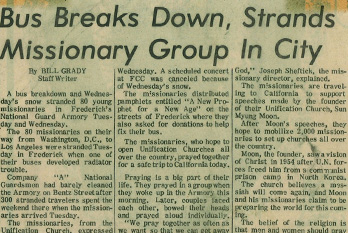

Pease (Herbers). (photo courtesy of Margaret Herbers) The newspaper clipping of our bus breakdown during a snowstorm

in Frederick, Maryland, en route to Los Angeles after Father's

February 19, 20, and 21 speeches at the Lisner Auditorium in

Washington, DC. This was one of various bus breakdowns that year. Stranded in Frederick MD photo February 1972.

For transportation, each team was given a retired school bus, which became our tabernacle for the next few months of wilderness life. When we set out at the end of March, only one of our teammates knew how to drive the bus, and while we were en route to Las Vegas, our team's first stop, Sam Pell pulled our bus into a truck stop to take a snooze, and Mr. Kim stood up and announced, "Father has chosen three lecturers. Let's see how they lecture."

Susan Hughes gave a gracious rendition of the Principle of Creation, and then it was my turn to lecture on the Fall of Man. From the front of the parked bus, the only face I could see clearly was that of a brother so soundly asleep that his eyeballs had rolled up so far that only the whites were visible. I breezed through the Fall of Man lecture in ten minutes, trying to keep from looking at the weird face. Mr. Kim cleared his throat and scratched his head, complaining that I had given too short a lecture but unable to think of anything vital that I had left out. Relieved, for the moment, I sat down and dozed off to dreamland myself.

We met our pioneer sister in Las Vegas, beginning a rhythm of a week with one pioneer and then traveling on to the next state and its pioneer. Pioneers who had sold tickets with us on city streets and had been working alone for weeks were delighted to see us arrive and even happier to see us leave.

We held street rallies and handed out fliers. We gave lectures in apartments and houses and rented halls. We squeezed 10 or 12 sleeping bags into tiny rooms and crammed into tiny kitchens to cook rice and soup. Pioneers who had sold tickets with us on city streets and had been working alone for weeks were delighted to see us arrive and even happier to see us leave.

David Kim placed special emphasis on the evening lectures. The podium and blackboard had to be arranged harmoniously, the chairs had to perfectly line up and members had to sit in strategic places. David Kim took the sentinel's position by the back entrance, scribbling furiously in a yellow legal pad, noting down every mistake to be held up for public review at morning service the following day.

Susan Hughes gave the Principle of Creation, I focused on the Fall of Man and Mission of the Messiah, and Perry Cordill taught history. Mr. Kim focused his attention on the Fall of Man lecture.

Lecturing under David Kim’s Watchful Eye

By this time I had been a member for almost two years. During that time, I had diligently studied Miss Kim's Divine Principle book, prepared numerous lecture outlines and lectured at various evening programs and workshops. While we were traveling with Father, President Young Whi Kim had given us many three-day cycles of Divine-Principle lectures based on the Korean textbook. Each of the four Korean missionaries Father had sent to America had written their own version of the Divine Principle. Perry, Susan and I had taken thorough notes of President Kim's lectures, and with the understanding that Father wanted to unify and elevate our understanding of Principle through these numerous lecture cycles, we based our lectures on notes from President Kim.

David Kim criticized every Fall of Man lecture I gave. Being a man of great intensity, Mr. Kim never gave a dispassionate critique. Each misspelling and each garbled phrase was noted. I'm a southpaw and each time I touched the chalk with my left hand, he would yell. I could accept that he was putting me through training. The greatest conflict was over the content of the lecture. I was a two-year member arguing with one of Father's earliest disciples over the content of the Principle. "I'm teaching what I learned from President Kim," I affirmed. Susan and Perry backed me up, but Mr. Kim retorted: "I don't care. What you said in your lecture is not true!" Almost daily we argued. In particular, the way I explained the “Tree of Life” bothered him, but I never quite understood how he thought it should be taught. Under the best of circumstances it was not easy to understand Mr. Kim's English; when he was shouting, it was impossible. If his life’s mission was David tackling Goliath, I was Joy hurling myself at David. After about three weeks, he surrendered and approved my lecture.

It became my responsibility to train other lecturers. When I believed they were ready, they would lecture in front of Mr. Kim. He never approved anyone's Fall of Man lecture on the first try. Sincere sisters would come to me in tears, insisting that they had followed my standard exactly. We went over the lecture word for word. Each one who persisted eventually received Mr. Kim's approval. As best I could tell, it was not precision of wording which David Kim sought but persistence and guts.

Lessons Learned from a Heavenly Soldier

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, our bus had broken down. Although fundraising was not a major focus, since we were receiving some support from national headquarters, we had to fundraise to pay a large repair bill.

I went around asking for money. I got a better response in New Mexico than in New York: a Cadillac dealer gave me a check for $25; the student council at the University of New Mexico allocated $55 to help us leave town.

I went around asking for money. I got a better response in New Mexico than in New York: a Cadillac dealer gave me a check for $25; the student council at the University of New Mexico allocated $55 to help us leave town.

The long bus trips were a welcome break from the routine. Mr. Kim taught us to make sam, a Korean-style ball of rice containing protein and vegetables and then wrapped in lettuce leaves. Before departing around mid-afternoon, we would make a big supply of sam. We would drive a few hours, stop at a park for a picnic supper and some horsing around until nightfall, and then pile back in the bus for a songfest that included favorite folk tunes, spirituals, or Broadway musicals. Around midnight, we would park the bus along the highway and roll out our sleeping bags on the grass to doze under the summer stars. Around dawn, a state trooper would rouse us with a stern lecture about camping only in campgrounds.

We would duly apologize, pile into the bus, and drive to the nearest greasy spoon restaurant, where we would wash up, drink some dreadful coffee and play the jukebox, joining John Denver in a boisterous rendition of "Country Roads." In high spirits we would greet our brother or sister in the next city.

We drove through Mississippi en route from Memphis to New Orleans and from New Orleans to Birmingham. We did not witness and teach there because the pioneer originally sent to Mississippi had remained in Phoenix, Arizona to replace a brother who was unable to handle the responsibility. The emptiness of the state called out to me, and when we reached our destination of Washington, D.C., at the end of July, 1972 I asked Neil Salonen, then president of the Unification Church in America, for permission to pioneer Mississippi.

One morning in Austin, Texas, Mr. Kim did not get out of his sleeping bag. Nobody saw him move all day. We went about our usual daily schedule, talking almost in whispers. The second morning he didn't rise either. I went to health food stores looking for Korean ginseng tea and placed a cup of hot tea by his nose, hoping the aroma would create a response.

Nothing happened. The third day he remained in bed as well. That evening he got up, dressed, and acted like normal. We were dying of curiosity. "What happened, Mr. Kim?" we asked.

"An army of Mexican devils came to invade heavenly soldiers," replied our valiant leader. "Since I am the commander, they had to get my permission first. The devil general came to me and I fought him. It took me three days to defeat him. Now the devil army is gone. Heavenly soldiers are safe."

Although it often seemed that Mr. Kim spent every waking moment haranguing and criticizing us, we realized that he would face all opposition, both spiritual and physical, and give his life, if that's what it took, to protect and defend us. Three years later, when I was assigned as a missionary in Latin America, I remembered David Kim's fearless example and set out on a new round of battles both physical and spiritual.

Edited by Ariana Moon.